Chatori Shimizu : for the love of shō

Do you know what is a “shō”, “Gagaku music” or a “Kigae”? Our label artist Chatori Shimizu, shō performer and specialist of this instrument explains his passion made of tradition…

Chatori, can you explain what is a shō?

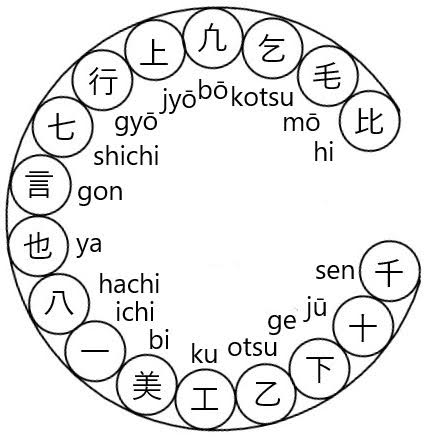

Shō is a Japanese free-reed mouth organ. The 17-bamboo pipes arranged in circular form is said to resemble a legendary phoenix resting its wings. Shō is an instrument used in Gagaku music, or the court music of Japan. Scholars believe that the instrument and the musical culture was brought into Japan from Tang Dynasty China and the Korean Peninsula around 1,300 years ago. After the Heian Period, new works for Gagaku instruments were rarely composed, and the music was performed only in the imperial court or in religious ceremonies. It is only after World War II, where this instrument was “re-introduced” to the general public, and both Japanese and non-Japanese composers began composing for shō.

As a chord instrument, it is extremely difficult for performers to play a fast, melodical passage on this instrument. Like the harmonica, players are able to produce the same sound(s) while inhaling and exhaling through the instrument. Changing the breath from inhale to exhale, or vice versa, is called “Kigae”. During the swell of the intensity building up to the “Kigae”, the time flow fluctuates in a distinct manner, giving Gagaku music a unique time identity [1].

How many of you know how to play this instrument?

This might be a little complicated. Aside from the court musicians at the Imperial Household Agency of Japan, there is no clear distinction between professional players and recreational learners. Many performers in religious affiliations, in fact, have jobs completely separate from their Gagaku practice. Nowadays, several ensembles in universities and religious organizations outside Japan offer opportunities to learn how to play the instrument in the context of Gagaku, thus, adding a small number of players to the list [2]. Few but a handful of performers exist in Japan and abroad, whose expertise is in the Western art music of the 20th and 21st Century.

When did you start to learn to play shō?

I began learning how to play shō in earnest in my undergraduate studies at Kunitachi College of Music in Japan. There, Mayumi Miyata, who is the pioneer in bringing this instrument to Western art music, was teaching shō in the contexts of Gagaku and also contemporary music. Afterwards, I was part of the Columbia Gagaku Ensemble, as well as experienced group training in a Japanese temple in Tokyo. I need to give credit to a Danish friend of mine, who happened to be an exchange student when I was at Kunitachi. He was the one who pulled me into the world of Gagaku.

You seem very active in the promotion of the shō worldwide. How is this Japanese instrument welcomed abroad?

As a researcher of “shō in the context of Western art music of the 21st Century”, I have had the privilege of traveling to more than thirty cities around the world to give lectures on the notation, instrumentation, and composition techniques of shō. Many who attend my lectures and workshops are composers who strive to compose for shō. Others include musicologists, ethnomusicologists, music theorists, as well as music lovers. I believe that Japanese instruments are welcomed abroad with a great interest. However, when this instrument is used in the context of Western art music, some performers may feel a dilemma to sense that the audience appreciate the rare instrument more than the musicality of the composition itself [3].

What are the preservation conditions required for the shō? Is it right that it needs a perfect temperature to work?

While performers inhale and exhale through the mouthpiece, their breaths moist the reeds inside the mouthpiece. A moist reed results in shō not being able to produce sounds. Performers must always heat up the instrument on top of a heater for ten to fifteen minutes before they perform. This is so that the inner cavity of the instrument is warmer than the temperature of their breaths. The performer must occasionally heat up the instrument on the heater during the performance too, as well as after. Therefore, modern-day performers carry portable electric heaters with them for performances.

[1] https://www.chatorishimizu.com/gagakudayorivol60

[2] https://www.chatorishimizu.com/ronsou47